Earlier this year, I wrote a post about the new first-semester bachelor course “Introduction to Computational Modelling for the Biosciences” at our institute. A quick summary:

- from 2017, the Biosciences bachelor study program will incorporate Computing in Science Education (CSE) into the different subjects

- a new course “Introduction to Computational Modelling for the Biosciences” will teach first-semester students python programming and basic mathematical modeling

- I am the lead organiser of the course (called BIOS1100) that started fall 2017

Yesterday, I finished grading the exam, so it is about time for a recap: how did it go?

The basics

There were 200 students present at the first of the weekly lectures.

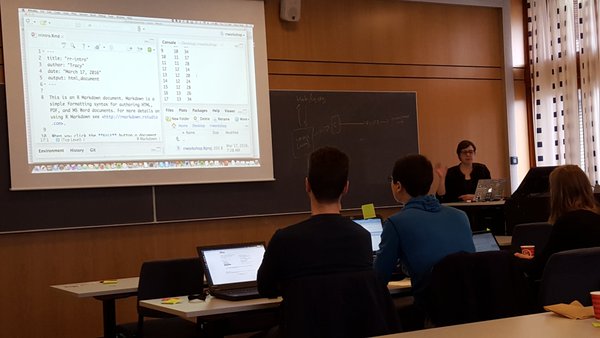

Each week, they would have a four-hour datalab session in the new ‘bring-your-own-device’ teaching room, where 60 students would sit in groups of 6 at hexagonal tables, with for each table a big screen available that any student could connect to from their laptop (all screens could project what was shown on the central screen, or on any of the other screens, really fantastic).

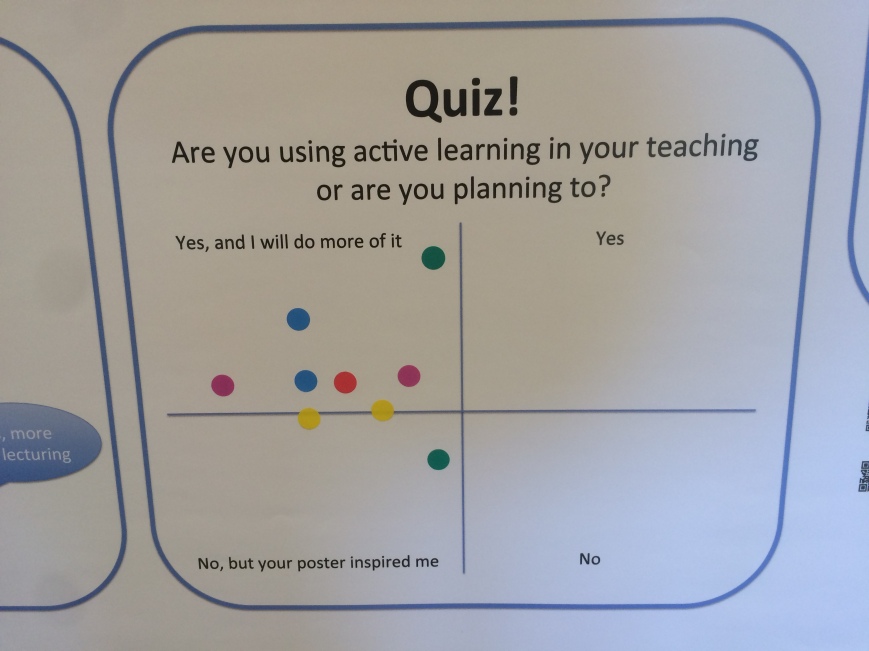

A typical datalab would start with formative assessment in the form of multiple choice questions (see ‘Peer instruction through quizzes’ in this blog post). This was often followed by ‘Computer Science Unplugged‘-type activities, pen-and-paper exercises to introduce programming concepts. Then they would work on programming exercises.

The programming environment we used was Jupyter Notebooks, accessed through a JupyterHub instance built for this and similar courses at the university. Exercises, and solutions the following week, were handed out as notebooks. Students were supposed to deliver one assignment, as a notebook, each week. I’m quite proud of the fact that we were able to deliver the course book chapters not only as PDF files, but also as Jupyter Notebooks, with runnable code (the notebooks were stripped of code output, and students were suggested to ‘run’ the notebook interactively while studying it). More on that another time…

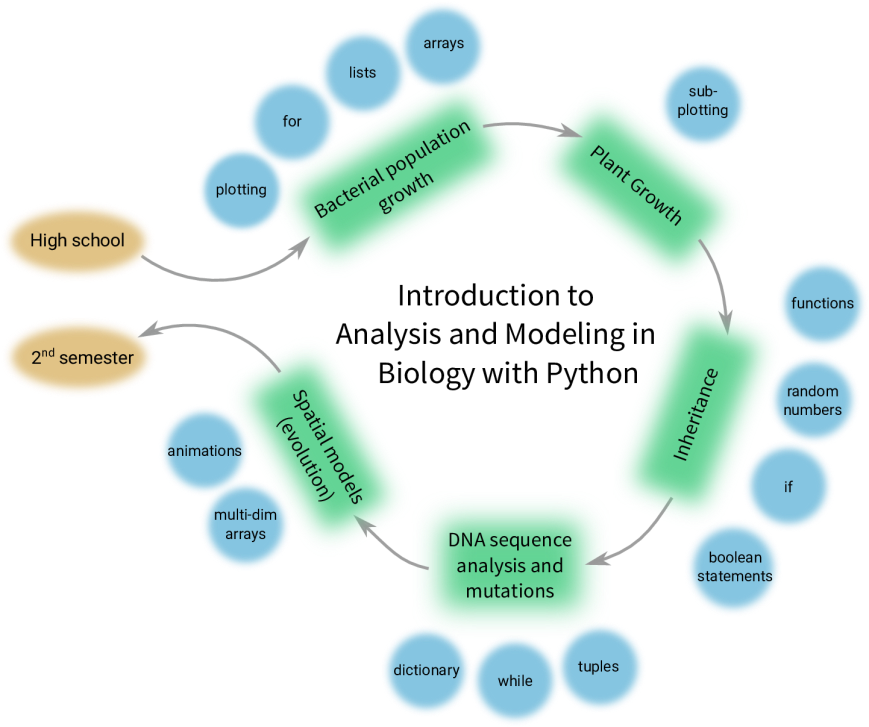

Curriculum and book

The figure below gives a broad overview of the structure of the book, a structure that was followed during the course. The philosophy for the book, and the course, was not teaching lots of Python first and then showing how it can be useful to solve biological problems, but introduce the biological problems first, and the Python concepts needed to solve them right after that. This way, all the learning of Python happened in the context of the Biology. The course book and materials will be published (Open Access!) in 2018.

Challenges

In my previous post I identified a number of plans and challenges I had in advance of the first course edition, and I will comment on them here.

Ground the material in biology

I wanted examples and exercises to be using data and questions that the students can relate to, given that they are studying biology/biosciences. This was implemented to a large extent, and I feel this worked quite well.

Build bridges with other courses

In preparation for the course, multiple ways were discussed to build a bridge with the Cell- and Molecular Biology course the students were taking the same semester. Students used Python to plot some of their laboratory measurements, calculated resolutions for different microscope lenses, digested the same DNA that they were going to digest using restriction enzymes in the molecular biology lab, in silico with Python. Students responded positive to having the exercises being relevant for their field of study, as well as seeing material used in both courses.

Use methods and create an environment that enhance learning

I am generally very happy with the choice of the Jupyter Notebook and the course room. There were no software installation issues and having a completely similar online environment (through JupyterHub) for all students, to which I could easily push new material, made organising the course much easier. There were some technical difficulties with the JupyterHub implementation – we were the first course to use it and ran into some unfortunate downtime, leading to understandable student frustration.

I had intended to use a ‘flipped classroom’ model, but did not manage to find a good way to make sure students had studied the relevant material from the book in advance.

Build a community of learning assistants

I had 19 learning assistants, master student and PhD students. Recruiting them happened rather late, which prevented me from having more than one meeting with them to prepare them for the course. But they were an enthusiastic bunch, and worked hard with the students. Much of the learning that happened was thanks to them. I struggled to really built a community, not many showed up at the (voluntary) weekly meeting.

Challenges I had identified in advance

- the motivational aspect: these students chose to study biology, not programming. Although I have not done a careful analysis, talking to students told me many saw the relevance of the course material for their studies in general.

- one goal for the study program is to continue learning and implementing CSE in the student’s next semesters. So far, in the student’s second semester, they will meet Python again in two of the three courses they take. In the third semester, they switch to R in the statistics and evolutionary biology courses.

Challenges that became apparent during the course

Exercises

A big challenge with any (totally) new course is that much, or all, of the material needs to prepared for the first time. A lot of this work was done before the course started, but unfortunately, not many exercises were ready beforehand. This led to me spending most of my time during the semester preparing exercise notebooks. This situation had several drawbacks: students and assistants did not have access to next week’s exercise material until the first day it was going to be used in class. I could not spend much time interacting with the students during their datalabs. It was also quite stressful.

Teaching programming successfully to new students

Around two-thirds into the course it became clear that a significant fraction of students felt they did not understand much, or anything, of the Python programming that was taught. The book was too difficult for them, many exercises too challenging, the format simply did not work for them. For the more mature students (that had studied elsewhere before) or those more or less familiar with programming, the format worked very well, but not for the rest. I’ll admit that this came as a bit of a shock, and I felt somewhat terrible about it for a while. In reflecting on his, I then posted this tweet, that I’ll explain here:

When I first thought about how to organise the teaching for this course, I strongly believed that the Software Carpentry approach of live-coding would be the best way to do it – it is after all how I do most of my teaching. With live-coding, an instructor or teacher does programming in real time and students in the room follow along, performing the same programming themselves – intermitted with many hands-on exercises. But at some point I started to worry live-coding wouldn’t scale to the 60 students present in the datalab, let alone the 200 students during lecture. Consequently, I dropped live-coding as a possible approach to teaching Python for this course.

When I discovered that many students were not learning the material, I decided to switch gears and go back to the live-coding approach. I announced that we were going to skip the material of the last two chapters of the book, and replace the remaining datalabs with repeat-teaching of the programming concepts. I did this through live-coding with the students, and also (finally) found a set of hands-on exercises that were very good for practicing more. The last three weeks of teaching were done in this way, and around 60-70 students came to these sessions. Feedback from the students was very positive: many were relieved and thankful, and felt they finally understood what this programming business was about. Interestingly, a handful of students were disappointed that the last part of the course material was skipped and asked whether they could still get access to it. In the words of the study-administration: “students never ask for more material, but for this course they did…!”.

In conclusion, I can only repeat “I thought the Software Carpentry live-coding approach wouldn’t scale to a large undergrad Python course and that I could do without it. I was 2x wrong”.

Exam results

So how did the students do? 180 students were allowed to take the exam, and 169 did. 80 % passed the exam, with an average C grade (scale A-F). From looking through the results, I saw a lot of learning has happened – although quite some misunderstandings remained. I decided that these results are actually not too bad for a first edition, and I’m actually quite happy with them.

Next time

I was recently asked what the biggest changes are that I want to make for the next time the course is taught (fall semester of 2018). Here was my answer:

- add another course responsible: courses are supposed to have two people in charge, and for this course, so far it has only be me. This is partly due to a lack, at least currently, of permanent staff at our institute with enough Python programming competence. Nonetheless, I will need a ‘buddy’, if only to enable me to get sick in the middle of the semester. I also hope this person can help strengthen the mathematics aspect of the course, which did not recieve enough attention this first time

- use live-coding from the beginning: I am considering dropping the lectures (which I did not manage find a good format for anyways) and start datalabs during the first weeks with live-coding, perhaps even for the entire course. It can’t just be me doing all the live-coding, I’ll have to recruit and train learning assistants to take part of this work too

- have exercises ready before the semester starts, implying quite bit of work needs to be done during next spring semester

All in all, organising this course has been (one of) the biggest and demanding projects I have ever undertaken, but I don’t regret one second accepting the challenge. The current generation of students will meet big datasets and complex analysis and modelling (Machine Learning! Artificial Intelligence!) whatever they end up doing in their professional lives. I am very proud to be a part of a (larger) effort to make sure they will be prepared for this once they graduate from our university.